The Synallagmatic Theory of Contract

One of the chapters in Divisions of Law will focus on Bodin's emerging theory of contract in the Juris Universi Distributio, partly to give some sense of how far Bodin followed the work of the humanist jurists that von Savigny would later call 'die Systematiker.' One of the most notable of these academic jurists was François Connan (1508-1551) whose Commentariorum Iuris Ciuilis was one of the first daring attempts to reorganize the whole body of civil law according to what might have been regarded a more logical, accessible pattern. Connan, like some of his contemporaries, were striving to achieve the Ciceronian ideal of a ius civile in artem redigendo - 'civil law reorganized into a system.'

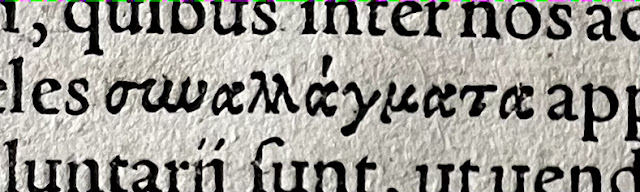

Connan's treatment of contracts is particularly noteworthy, for an Aristotelian idea he introduces in Book V:

|

| Connan, Commentariorum Iuris Civilis (1562) V, 1 p.474 (Photo: Daniel Lee, 2023) |

All genuine contracts, Connan declares, must fundamentally take the shape of what Aristotle once called 'synallagma' (= mutual exchange or benefit), a reference to Nicomachean Ethics V which discusses, in part, justice in commercial transactions and performance of contractual agreements - commutative justice. If that element of mutual exchange is lacking, then the transaction is not (according to Connan) properly contractual, a position that controversially excludes a range of unilateral contractual forms that, for centuries, had been recognized as legally valid and enforceable.

Connan was thinking of this passage in the penultimate book of the Digest, De verborum significatione:

|

| D.50.16.19 (Photo: Daniel Lee, 2023) |

The examples that are usually invoked in connection with synallagma are noteworthy: emptio-venditio (Sale), locatio-conductio (Hire), Societas (Partnership). These are all consensual contracts that were enforceable by specific remedies, such as the Actio Empti, the Actio Locati, and the Actio Pro Socio.

But Connan isn't interested in these - it's obvious these are contracts with legal force. What about formless agreements - pacts, promises, and unnamed (or 'innominate') contracts? Are these contracts as well? Connan has a tidy answer - there must be some synallagmatic or bilateral structure binding the parties to the agreement. If there is such a synallagma, then it is a contract. If not, not.

This was the background to Bodin's own classification of contracts in the Juris Universi Distributio. Bodin's own approach, while clearly influenced by and responding to Connan, also departs from Connan's treatment of synallagma.

The genus for all species of contracts is 'conventio' ( or agreement):

It is a genus that admits of three basic species:

|

| Bodin, Juris Universi Distributio (Photo: Daniel Lee, 2022) |

It's hard to see in the photo: The three species of contracts are:

1. Consensu nudo facta - the most important illustration of which is the 'pollicitatio' which in classical Roman law was generally unenforceable and not treated as having the same legal effect of a contract

2. Stipulatione - this is the 'stipulatio' of Roman law, the verbal obligation binding promissory to stipulator simply by exchange of formal words. This becomes the 'default' standard contractual form in classical Roman law. Bodin, however, sees this as comparable to the pollicitatio because of its basic promissory structure: It is an agreement that is 'praeter consensum.'

3. Contracta facta cui synallagma inest - It is here that Bodin borrows from Connan's basic thesis that the contractual form is ultimately bilateral or 'synallagmatic.' Most contracts -onerous and gratuitous - fall under this third label, but it is unmistakably an analysis that originates in Connan's original synthesis.

This is also a good example of Bodin's broader purpose for this work. Bodin is trying to develop a system for comparative law, not simply a pedagogical tool for Roman law. This gives him license to move away from the strictures in Justinian and Gaius, and possibly even imagine another way of organizing a legal system - something that is achieved in later centuries by Domat, Stair, and Pothier.